この記事の原文 [2]はMeta.mkに掲載されました。グローバル・ボイスとメタモルフォーシス財団とのコンテンツ共有合意に基づき、編集を加えたものを以下に掲載します。インタビュー回答部分に張られた全てのリンク先は、Meta.mkにより追加されたものです。(訳注:日本語訳に際し、一部リンクを追加・編集しています。)

キース・ブラウン [3]は、アリゾナ州立大学 [4]の政治学・グローバルスタディ学部の教授である。ロシア、ユーラシア、東ヨーロッパの研究を行うメリキアン・センターの所長も務めている。シカゴ大学で人類学の博士号を取得し、主にバルカン諸国を対象に、文化、政治、アイデンティティに関する研究を行っている。

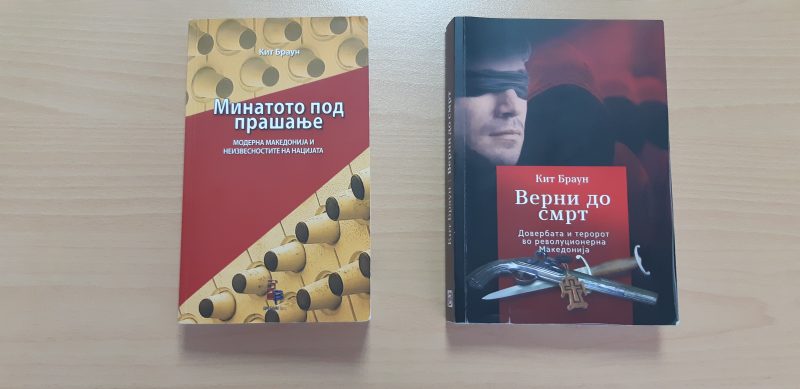

バルカン地域におけるエスノナショナリズムについて、またナショナルヒストリーの役割についてのブラウン教授の広範な調査は、彼の著書『疑わしき過去:近代のマケドニアと国家の不確実性(原題:The past in question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation)』(2003年)、『忠誠から死へ、マケドニア革命の信頼と恐怖(原題:Loyal unto Death, Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia)』 (2013年)にその一部が収められている。両書は(訳注:英語からマケドニア語へ)翻訳され、北マケドニアでも一般入手が可能になっている。

ポータルサイトCriThink.mk [5]が行ったインタビューで、ブラウン教授は、歴史を学ぶ上でクリティカル・シンキングを用いることの重要性を語った。

CriThink:歴史学と人類学にクリティカル・シンキングを適用することは、どのように重要なのでしょうか。

Keith Brown (KB): Critical thinking is very important in both history and anthropology. Skeptics and naysayers sometimes dismiss our methods as “soft” or trot out tired clichés like “history is written by the winners.” But evaluating and comparing sources, and weighing how cultural and social factors impact individual decisions, are essential components of both disciplines. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, historians and anthropologists recognize that meanings and horizons shift over time and across space.

This is especially important in the study of nationalism—a mode of political organization and identity formation that contributed to the break-up of multiconfessional empires in the 19th century, and which often seeks legitimacy by claiming ancient roots. What makes it more complicated is that most nation-states place a high premium on communicating to their citizens a strong sense of shared history that distinguishes them from others. Often, it is easier for people to see the inconsistencies and distortions in their neighbors’ versions of the past, than to question or closely scrutinize the history that they think holds their own society together.

Critical thinking demands, as an early step, recognition of one’s own blinkers, prejudices and areas of ignorance. It also benefits from dialogue in which participants check their egos and agendas at the door, and measure success not by the points they score, but by the new ways of seeing they have helped generate for themselves or others.

キース・ブラウン(以下、KB):クリティカル・シンキングは、歴史学と人類学、両方において非常に重要です。懐疑派や否定派の人々は我々の手法を「手ぬるい」と呼んだり、「歴史は勝者によって作られる」といった陳腐な表現を持ち出して、取り合わないことがあります。しかし、複数の情報源を評価し比較すること、文化的・社会的な要因が個人の決定に与える影響を見極めることは、両学問分野において不可欠な構成要素です。更に、これはおそらく最も重要なことですが、歴史学者や人類学者は、意味付けや境界付けは時間や場所によって移り変わるものであるという認識を持っています。

これは、特にナショナリズムの研究の際に重要です。ナショナリズムとは、政治組織化と自我形成のひとつの様態であり、19世紀に多宗教を持つ国々を解体することに寄与しました。その正当化のために、しばしば古代のルーツが主張されました。大半の国民国家 [6]では、自分たちとそれ以外を区別する強力な共通の歴史観を自国民へ広めることが非常に重要視されており、このことがナショナリズムをより複雑にしています。人間にとって、自分たちの社会を団結させている(と思っている)歴史について疑念を抱いたり、それを丹念に精査することよりも、近隣住民側から語られる過去についての矛盾やゆがみを見つける方が、往々にして簡単なのです。

クリティカル・シンキングの第一歩として要求されるものがあります。自らの目を曇らせるものは何か。先入観は何か。無知の領域とは何か。これらを認識することです。次のような対話手法も有益です。参加者は、自身の抱いているエゴや隠れた意図をまず確認してから、対話の席に着きます。参加者にとっての成功の尺度は、何点獲得したかではありません。参加者らが協力し、自身のためあるいは他人のために新しい物の見方を生み出すことができれば、その対話は成功です。

CriThink:バルカン諸国の大半の政治体制は、「ナショナルヒストリー」という概念の推進にこだわっているようです。この「ナショナルヒストリー」は、「前向き」なものを選び取り「後ろ向き」なものを排除して得た「事実」に基づいており、いずれ公教育の教科書に掲載する公式な物語を創作することあるいは守り通すことを、その目的としています。こうした独善的なアプローチが、過去200年間、「自分たち以外の人々」への圧制を正当化するためにしばしば使用されました。歴史を扱う方法はこれ以外にもあるのでしょうか。

KB: History is an incredibly rich domain of study. In 2015, oral historian Svetlana Alexievich [7] was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for her work chronicling citizens’ voices from the end of the Soviet Union. Organizations like EuroClio [8]—to which many history teachers from the Balkans and Eastern Europe belong—promote the study of global history, and encourage members and students to explore social, cultural and economic history. Courageous and open-minded historians are often leading critics of the exceptionalism on which national history is founded—including in the United States, through efforts like the 1619 project. [9]

I think that these kind of approaches have enormous potential to transform people’s understandings of the past, and prompt reflection on how the present will look from the future. I am particularly excited by the promise of microhistory [10], as pioneered by Carlo Ginzburg [11], which draws out the broader human significance from the close study of an event or community.

KB:歴史は、非常に豊かな研究領域なのです。オーラル・ヒストリー(口述歴史)を実践するスヴェトラーナ・アレクシエーヴィチ [12]は、ソ連崩壊時からの市民の声を記録した功績で、2015年にノーベル文学賞を受賞しました。バルカン地域や東欧の歴史教師が多く所属するユーロクリオ(EuroClio) [8]などの組織も存在し、グローバルな歴史の研究を推進するとともに、社会史、文化史、経済史の探求を組織員や学生らに奨励しています。勇敢で開けた考えを持つ歴史学者らが、例外主義への批評家を牽引することもよくあることです。例外主義はナショナルヒストリーの基盤となるもので、米国における1619プロジェクト [9]等の取り組みが一例として挙げられます。

私は、これらのアプローチには莫大なポテンシャルがあると思っています。人々の過去への理解をすっかり変えてしまう可能性や、現在の姿が将来どのように見られるのかについて熟考を促す可能性を持っていると思うのです。特に私が強い興味を惹かれるのが、カルロ・ギンズブルグ [13]が拓いたミクロストリア(マイクロ・ヒストリー) [14]から得られる成果です。ミクロストリアとは、ひとつの出来事やコミュニティについての詳細な研究をもとに、より幅広い人間的意義を導き出すものです。

CriThink:先生の著書『忠誠から死へ、マケドニア革命の信頼と恐怖』の中で、入手可能な歴史的資料には信頼性が欠けていたり、バイアスが掛かっているという課題に直面したとあります。例えば、ギリシャのマケドニア闘争博物館 [16]にマイクロフィルムとして保存されているイギリス領事の通信文書であったり、北マケドニア国家アーカイブ [17]に保存されている、革命を生き延びた高齢者が1948年から1956年にかけて新しいマケドニア国家に提出した年金申請書であったりです。これらの記録の中から有用な情報を抜き出すという難題を、どのように処理されたのでしょうか。

KB: I first read many of these sources while I was a graduate student in anthropology. Conscious that the Ilinden Uprising [18] of 1903 had been interpreted differently by scholars for whom the correct context was Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian, Albanian, Yugoslav, Ottoman, Balkan or Macedonian history, I wanted to get as close to the period as I could, by engaging closely with sources that, in one way or another, stood outside these frames of reference.

I was struck, for example, by the fact that according to the records of the National Archive in Skopje, only a handful of scholars had sought access to the Ilinden dossier of biographies. My understanding was that these sources were discounted because, self-evidently, they were self-interested. The British, French, German and American diplomatic and consular records from Ottoman Macedonia, by contrast, are often treated as wholly dispassionate, objective and clinical accounts, as if their authors were scientifically trained medical professionals, diagnosing the ills of an empire on its death-bed. In writing “Loyal Unto Death,” I took an alternative, subversive approach toward these two sets of sources. Whether or not individual pension-seekers amplified their own roles, or edited out those elements that might weaken their case for state recognition, their accounts drew from their own or their age-mates’ experiences and understandings. No-one lied about the organizational structure of the revolutionary organization, the methods of recruitment, or the logistics of acquiring weapons or distributing information and supplies: what would be the self-interest in doing so? Thus they provide us, individually but even more so in aggregate, with a sense of the shared day-to-day experience of participation in a resistance and rebellion.

British consular accounts, often read as if magisterial, reflect their individual authors’ biographies, perspectives and access to sources: Alfred Biliotti [19] was a naturalized British citizen born in Rhodes who had worked his way up from the position of dragoman and had close ties with Ottoman and Greek authorities, whereas James McGregor knew Bulgarian and expressed the view that the Organization commanded strong support. Their accounts diverge or clash. This is not to say that all sources or accounts are equally valid or suspect. It is rather to argue that we need to get past our own cultural preconceptions, whether they tell us “peasants lie” or “diplomats are cynical careerists,” and remain alert to the ways they can surprise us.

KB:私が初めてこのような資料と向き合ったのは、文化人類学を研究する大学院生の時です。多数の資料を読み、1903年のイリンデン蜂起 [18]の解釈のされ方が学者によって異なることに気づきました。学者ごとに、正しい文脈となるのはギリシャの歴史であったり、あるいはブルガリア、セルビア、アルバニア、ユーゴスラビア、オスマン帝国、バルカン地域、マケドニアの歴史であったりします。私は、この時代について可能な限り深く掘り下げてみたくなりました。そこで、あれこれの手段を用い、このような参考文献の枠組を越えたところにある資料に取り組みました。

結果は衝撃的でした。例えば、スコピエ市の国家アーカイブの記録によれば、イリンデン蜂起関係者についての人物資料を参照しようとした学者はごく一握りだったという事実がありました。私の理解では、こうした資料は、明らかに自己の利益に基づくものであり、それゆえに軽視されたのです。一方で、イギリス、フランス、ドイツ、米国からの外交官や領事が、オスマン帝国統治下としてのマケドニアで残した記録については、全体的に冷静で、客観的で、論理的な記述として扱われていることが多いのです。あたかも、これを書いた人間は科学的な訓練を受けたプロの医師であり、死の床にある大帝国の病気を診断しているかのような扱いでした。自著『忠誠から死へ』では、私はこの2種類の情報源に対して、まったく新しい、破壊的なアプローチを行いました。個々の年金申請者が自身の役割を強調して述べていようといまいと、あるいは国の承認を受けるにあたり不利になりかねないとしてこれらの要素を省いてしまっていたとしても、彼らの記述は、自分自身や同年代の仲間たちの経験や認識をもとにして引き出さたれものです。革命組織の構造について、仲間集めの手段について、あるいは武器入手、情報伝達、物資供給の手順について、嘘をつく者は誰もいませんでした。嘘をついたところでいったいどんな自己の利益になるというのでしょうか?だから、一つ一つはなおのこと総体としても、これらの資料は抵抗と反乱に加担した日々を我々に生き生きと物語っています。

イギリス領事による記述は高圧的な印象を与えることがしばしばありますが、個々の書き手の人生経験や物事の捉え方、どのような情報源が利用可能だったのかが反映されています。例えば、アルフレッド・ヴィリオッティ [19]は、ロドス島生まれで、オスマン帝国やギリシャ当局と緊密な関係にあったドラゴマン(通訳官)としての職から昇りつめ、イギリスに帰化した人物です。一方、ジェームス・マックレガーはブルガリアを知る人物であり、組織が強固な支持を命じたという見方を表明しています。彼らの記述は異なり、互いにぶつかり合っています。だからと言って、あらゆる資料や記述は等しく無効であるとか、疑わしいということではありません。それよりむしろ主張すべきことがあります。たとえ「百姓は噓をつくものだ」、あるいは「外交官とは出世第一主義のひねくれ者だ」、などと言われたとしても、我々自身が抱える文化的先入観を克服する必要があることです。そして、こうした先入観がどんな手段で意表を突いてくるのか、常に注意を怠らないことです。

CriThink:さまざまな記録やその翻訳版は存在せず、あるいは検閲され、複雑に絡み合い、互いに対立しています。さらには、当時使われていた言葉の中には意味が変わってしまっているものもあります。実用的なタイムマシーンが存在しない以上、これでは歴史上の人物の「国民意識」を正確に突き止めることは難しいことです。地域全体として、このような問題を解決するためにはどのようなクリティカル・シンキングのスキルを培う必要があるのでしょう。

KB: In “The Past in Question,” I chose to use the language of the British consular sources rather than update or modify it, and to try to translate sources in Greek and Bulgarian into the English of that time, rather than of the early 21st century. I thus used terms like “Bulgar,” “Arnaut,” “Mijak” and “Exarchist” seeking in this way to remind readers of the very different world of the late nineteenth century; when “Greece” referred to a territory roughly half the size of modern Greece; when only a small fraction of people who would call themselves “Bulgars” owed loyalty to the Ottoman-administered “Bulgaria” with its capital in Sofia; when the Sultan sought to restrict the use of the Albanian language, and the term “Macedonia;” and when the prospect of an alliance of convenience between the ambitious nation-states of Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece to carve up and nationalize Ottoman territory surely seemed absurd to most.

For me, critical thinking demands, paradoxically, that we try to unlearn what actually happened since the period we are trying to understand; or at least, allow it to strike us as surprising or at least non-inevitable. This then concentrates our attention on the factors that drive outcomes. It also liberates us from the illusion that figures in the past—like Ilinden-era figures Goce Delchev [21], Nikola Karev [22], Damjan Gruev [23] or Boris Sarafov [24]—imagined their own identity in terms of the nationalisms of their future.

KB:私は『疑わしき過去』の中で、イギリス領事の資料に出てくる言葉を、現代に合わせたり修正したりせずに使用することにしました。また、ギリシャ語やブルガリア語で書かれた資料は、21世紀初頭の英語ではなく、当時の英語に翻訳するよう努めました。このため、「Bulgar」「Arnaut」 「Mijak」「Exarchist」といった単語を使用しています。19世紀末のまったく異なる世界を読者に感じてもらおうと考えたのです。当時、「Greece(ギリシャ)」という語が指していた領土は、現代のギリシャのおよそ半分くらいの広さでした。ごくわずかな人々だけが自身を「Bulgars(訳注:ブルガリア民族を指す語)」と考え、ソフィアを首都とするオスマン帝国統治下の「ブルガリア」に忠誠を捧げていた時代でした。スルタンがアルバニア語や「マケドニア(訳注:マケドニアは、現在のギリシャ、北マケドニア共和国、ブルガリアの3ヵ国にまたがる地域である)」という単語の使用を規制しようと狙っていた時代でした。そして、国民国家づくりに意欲的であったブルガリア、セルビア、ギリシャが、オスマン帝国領から分離した国家設立を目指し、一時的な便宜協定を結ぶなどという見通しは、ほとんどの人にとっては間違いなく荒唐無稽に感じられた時代でした。

私が考えるに、逆説的ですが、クリティカル・シンキングが要求するものは学習棄却(アンラーニング)です。理解しようとしている時代以降に実際に起こった出来事について、我々が学習棄却に努めることです。あるいは少なくとも、こうした実際の出来事について驚きを感じながら、または避けられたかもしれない出来事だったという感覚で受け止めることを許容することです。こうすることで、結果を生み出したファクターに集中的に注意を向けることができます。また、我々が囚われていた幻想からも解放されます。幻想とは、イリンデン蜂起時代のゴツェ・デルチェフ [21]、二コラ・カレフ [22]、ダミアン・グルエフ [23]、ボリス・サラフォフ [24]などの過去の人物が、自身の将来にそびえるナショナリズムの観点から想像した、彼ら自身のアイデンティティのことです。

[25]

[25]マケドニア語版『疑わしき過去:近代のマケドニアと国家の不確実性』の宣伝を行うキース・ブラウンと、歴史家のイレーナ・ステフォスカ。2010年12月。写真 [26]:ヴェンチョ・ダンバスキ。 CC BY-NC-SA.

CriThink:しかしながら、この種の問題は、さながら「すべり坂論法」、すなわち一歩踏み出せば坂道を転がるように危険な方向に進むという現象によって、国際的な論争の的になりつつあるようです。例えば、ゴツェ・デルチェフ(ブルガリアー北マケドニア)、二コラ・テスラ [27](セルビアークロアチア)、スカンデルベグ [28](ギリシャーアルバニア)、ニェゴシュ [29](モンテネグローセルビア)、マルコ王 [30](北マケドニアーセルビアーブルガリア)などです。こうした問題を、単に折り合わない国同士が権力に基づいて争っているというレベルではなく、いくらか高次元で客観的なレベルへと引き上げて解決していく方法は何かあるのでしょうか。

KB: Social scientists, including historians (and I’d include myself in this assessment) don’t always keep up to date with developments in other disciplines and fields. This manifests itself in approaches rooted in the conventions of 19th century Newtonian sciences, with a focus on breaking down complex reality into experimental-size pieces, where we can test hypotheses in an “either/or” mode to determine cause and effect, the rules of energy transfer and transformation, and so on. Contemporary theoretical and experimental science, though, have moved far beyond this paradigm; into the world of quarks, bosons and quantum mechanics, where non-specialists can barely follow. Ask the average person where they stand on the wave-particle duality [31], and you’re probably in for a short conversation. It requires thinking in “both/and” terms that demands effort, and also a realignment of deeply held common-sense. But this lack of public understanding doesn’t prevent physicists from pursuing their work and generating new insight into the workings of the universe.

Balkan history has been shaped by the territorial ambitions and disputes of the last century, and so has become a zero-sum game [32]; it also has quasi-religious aspects, insofar as current debates reveal an implicit concern with purity and pollution underlying accusations around loyalty and betrayal. Grievances and disputes escalate; and (to pursue the game metaphor) there is no mechanism, in this case, by which both sides would agree to invest a referee with the authority to call the game fairly; the stakes are seen as too high.

An alternative view would be that the dispute over Goce Delchev’s “true” identity, for example, is a classic case of the prisoner’s dilemma game [33]; in which both sides fear that by surrendering their claim to ownership they will lose and the other side will win (Bragging rights? Prestige? The mantle of “true” nationhood?), but the consequence of their refusal to acknowledge ambiguity is that both sides are seen as intransigent or blinkered in the wider community of nations.

KB:これは私自身にも言えることですが、歴史学者を含む社会科学者全般というものは、必ずしもいつでも他の領域や分野の最先端に通じているわけではありません。このことは、19世紀ニュートン主義科学の紋切型なアプローチ手法に表れています。ここでは「AかBか」という観点での仮説のテストができるように、複雑な現実世界を実験可能なサイズへ細分化することに焦点が当てられています。そして原因と結果や、エネルギーの移動と変換の法則など、様々なものが確定されます。しかし、現代の理論科学や実験科学はこのようなパラダイムより遥かに先へ行ってしまっています。クォーク、ボソン粒子、量子力学の世界において、専門外の人間にとっては後を追うのが精一杯です。ごく普通の人間に、粒子と波動の二重性 [34]についてどのような立場をとられますかと尋ねたなら、おそらくは短い会話で終わるでしょう。これには「AでありBでもある」という観点での思考が必須で、努力が要求されるとともに、深く根ざしてきた常識を再調整しなければなりません。しかし一般の人々の理解が不足していても、物理学者らは妨げられることなく研究に取り組み、宇宙の営みの中へ新しい見方を創り出していきます。

バルカン地域の歴史は、過去100年間の領土に絡む野望や論争によって形作られ、ゼロサムゲーム [35]となってしまったものです。忠誠と背信を取り巻く様々な非難の根底には、純粋と汚染についての潜在的懸念があるということを、昨今の論争が露呈させており、この限りにおいては半宗教的な側面もあります。不満の声や言い争いはエスカレートしていきます。しかも、(ゲームの比喩を使うなら)この場合、公平に試合を中止する権限を審判に委ねることで両者が合意する、といった心理は働きません。それはリスクが高すぎるからです。

ひとつ新たな見方となりうるとすれば、例えばゴツェ・デルチェフが「本当は」何者だったのかという論争は、「囚人のジレンマ [36]」ゲームの典型例です。このゲームでは両者とも、所有者としての主張を放棄することで、こちらが負けてあちらが勝つことになる(戦利品は、自慢する権利?名声?「本物の」国家に被せる立派なマントでしょうか?)のを恐れています。しかし、曖昧性を双方が認めたがらない状況は、より広域の国々のコミュニティの中では、両者とも非妥協的あるいは偏狭であると見られてしまう結果を招くのです。

CriThink:ルワンダや旧ユーゴスラビアでは、大量虐殺や戦争犯罪を伴う衝突を終結させるために法廷が使われましたが、バルカン地域における事態のエスカレートを避けるために、これに似た「国際科学法廷」のようなものを構築していく必要があるのでしょうか。

KB: I don’t see value in an external tribunal offering some authoritative closure: for me, that’s not how history (or science) work. All findings are contingent and provisional: they are contributions to an ongoing exchange, the ultimate goal of which is not to set some conclusion in stone, but provide material that can open new horizons and perspectives.

KB:私は、外部の法廷がある種の権威をもって終結を差し伸べることには価値を見出しません。それは歴史(あるいは科学)のやり方ではないと私は考えます。発見された物事は全て、偶然が生んだものであり、一時的なものです。これらは、現在進行形の交流に役立つものです。発見された物事が究極的に目指すところは、なにがしかの確固たる結論に行き着くことではなく、新たな地平や視点を切り開くための素材となることです。

CriThink.mk:、バルカン地域のメディアは、こと歴史に関して言えば、最も極端で二極化した国家主義的視点を増幅させる役割をしていることが多くあります。プロのジャーナリストが本来持つ民主主義を後押しするという役割とは裏腹です。このようなメディア界の本流の中へ、歴史についてのクリティカル・シンキングを組み込んで行く方法はありますか。

KB: My own fantasy solution is something like what a group of Macedonian youth leaders did in the second half of the 1980s with the Youth Film Forum (Mladinski filmski forum [37]), and set up learning opportunities through engagement with film, literature and other prompts. What would happen, for example, if Bulgarian and Macedonian historians and journalists watched “Rashomon [38]” together? Or undertook a joint project (perhaps with Albanian colleagues) on the economic, psychological and social effects of gurbet/pečalba [39]? Or conducted a close joint study of the United States 1619 project? I believe they would emerge with a shared vocabulary to address issues of contingency, ambiguity, trauma and structural violence that are shared across the Balkan region—and beyond.

KB:私自身が空想する解決方法は、1980年代後半にマケドニアの若い指導者のグループがユース・フィルム・フォーラム(Mladinski filmski forum [37])で行ったことと似たようなものです。映画、文学、その他さまざまな種類の活動を通じた学びの機会を立ち上げるのです。例えば、ブルガリア人とマケドニア人の歴史学者やジャーナリストらが一緒に『羅生門 [40]』を観たら何が起きるでしょう?あるいは、グルベットまたはぺカルバ [39](訳注:労働移民を意味する語)の経済的、心理学的、社会的影響についての合同プロジェクトを(ひょっとするとアルバニア人同僚と共に)引き受けたら?またあるいは、米国の1619プロジェクトについての詳細な合同研究を実施することにしたら?そうしたらきっと彼らは、バルカンやその他の地域にも同様に存在している、偶発性、曖昧性、トラウマ、構造的暴力といった問題へ、共に分かち合った理解言語で立ち向かうだろうと、私は信じています。

(訳注:記事中の著書の邦題は、訳者による試訳です。)