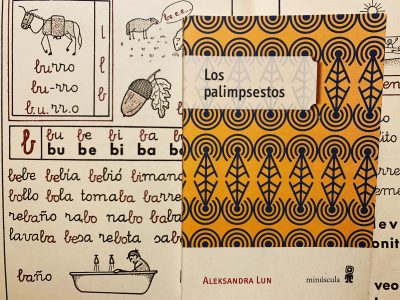

アレクサンドラ・ルンがスペイン語で書いた小説「ロス・パリンプセストス」のカバー 著者撮影 掲載許諾取得済

エクソフォニック・ライターとは「母語以外の言語で創作を行う作家」を指す言葉だ。人の往来が世界規模で多方向に拡大する21世紀にあって、非母語作家の増加は社会現象と言えるだろう。

先ず、明確にしておきたい事がある。それは物心がつく頃から多言語環境で育った作家と、成長してから他言語を習得し、大人になってから自分の意思で外国語で創作を行う作家は別者である。

前者の例としてよく引き合いに出されるのはウラジーミル・ナボコフだ。後者の例で現在の作家を挙げるならジュンパ・ラヒリだ。ラヒリはイタリア語の作家だが、ベンガル系アメリカ人で以前は英語の作家だった。

アレクサンドラ・ルン ミルナ・パブロビッチ撮影 掲載許諾取得済

そしてアレクサンドラ・ルンも後者の1人だ。ポーランド語を母語とするプロの翻訳者だが、ある日スペイン語で小説を書くことを思い立った。ルンがスペイン語を習得したのは19歳になってからで、小説そのものも言語の混交性に関する話だ。「ロス・パリンプセストス」は2015年にスペイン語で出版され、英語にも翻訳されている。ポーランド人作家チェスワフ・プレスニフスキイが南極に移住し、南極で話されている架空の言葉を習得して小説を書く話だ。

ルンへのインタビューでは、外国の言語を受け入れて創作を行う動機、そして自分の文化圏の外で作家となる事について話を聞いた。

訳注: パリンプセストは再利用した羊皮紙に書かれた文書のことです。羊皮紙は再利用可能で、消した元の文書も目に見えないだけで、復元して読み出すことができます。

フィリップ・ヌーベル (FNと略す): ポーランド語を母語とし、19歳になってからスペインで学資を稼ぐためにカジノで働きながらスペイン語を学び、今はスペイン語の作家として活躍されています。母語以外の言語に乗り換えて創作する理由は何でしょうか?

Aleksandra Lun: If we think about the Czech proverb that says that we live a different life in every language we know, I have had several lives, as I am sure many of Global Voices’ readers have had too. According to my calculations, I could be now 136 years old, which is frustrating since I don’t seem to be receiving any retirement benefits! The way I see it, there has been no linguistic shift, only the fact that in one of my lives I am a writer.

We can see languages as multiverses, a concept from a theoretical framework in physics called string theory. Like a multiverse, each language describes a different story, a story that happens simultaneously to all other stories. Writers are just the people who put those stories down.

アレクサンドラ・ルン (ALと略す): 知ってますか?チェコのことわざ。「覚えた言語の数だけ、何通りもの一生を生きる」って言うんだけど。これに従えば、グローバルボイスの読者同様、私は異なる人生をもう何種類も味わい、計算したところ私は136歳。しかも腹立たしいことに、年金らしきものは一切受け取った覚えはない。私の見立てでは、言語の乗り換えというものは存在せず、いくつもの人生のうちの1 つで、私が作家だというだけ。

物理学の世界では、宇宙が同時並行的に存在する考え方をひも理論と言うが、各言語の存在も同時並列的なもの。一つの出来事であっても、言語の世界では言語の数だけ異なった話が同時に発生してゆく。作家というのはただ、その話を書き留める人でしかない。

FN: ポーランド語でも作品を書くことはありますか?バイリンガルの作家やエクソフォニック・ライターによると、外国語で書くメリットは、作品と自分の間に距離を保てるので、母語で表現困難な事が外国語でなら可能という話をよく聞きます。

AL: For “The Palimpsests,” I researched into cases of authors who changed languages: illustrious immigrants like Samuel Beckett, Ágota Kristóf, Joseph Conrad, Vladimir Nabokov, Emil Cioran and others. I didn’t find any common denominator since they all had their own reasons not to write in their mother tongue. Some took a time-specific decision to change, others did it naturally. Some switched languages for personal reasons, others for commercial ones. Joseph Conrad used to say that he didn’t choose English at all – it was English that chose him. He also said that English was the only language he could have ever written in, while Ágota Kristóf claimed she would have written in any language. There is a variety of choices and motivations, and they are all legitimate.

I cannot say that I don’t write in Polish since in my translations I write in Polish all the time. But my muses talk to me in Spanish, so translating their voice into Polish would just be double work. Regarding the distance that writing in another language is supposed to create, I think it all depends on the relationship you have with it. To me, Spanish is the most natural choice. Using it is no stranger than brushing my teeth – I might not receive retirement benefits, but I am proud to conserve my own dentition.

AL: ロス・パリンプセストスを書くにあたり執筆言語を変えた作家の調査を行った。サミュエル・ベケット、アゴタ・クリストフ、ジョゼフ・コンラッド、ウラジーミル・ナボコフ、エミール・シオランなどなど、キラ星のように居並ぶ移民作家を調べたが、共通の理由と言うものはなかった。母語で創作を行わない理由は、人それぞれだった。ある時を境に使用言語を変えた者もいれば、成り行きでそうなった者もいる。自らの考えで変えた作家もいれば、金銭面でそうした者もいる。ジョセフ・コンラッドは自分が英語を選んだのではなく、彼は英語に選ばれたのだと言っている。また英語は自分が執筆できる唯一の言語だったとも言っているが、一方でアゴタ・クリストフは書く事ができるのなら、言語など選ばずにとにかく書くのだと言い切っている。

いつもポーランド語への翻訳を行っているので、ポーランド語で書くことだって無いとは言えない。でも詩の女神ミューズがスペイン語で私に語りかけてくれているのに、ポーランド語にわざわざ翻訳してから書き留めるなんてもったいない。外国語で創作することで生まれるとされる距離感について言えば、作者がその言葉をどう感じているかによって全く異なると思う。私にとってスペイン語は当然の選択で、毎日歯を磨くのと同じで考える前にそれを使っている。さっきの年金について不満は残るが、歯磨きの成果同様に、母語以外を知り、いくつもの人生を生きている事を誇りに思っている。

「ザ・パリンプセストス」英語版のカバー アレクサンドラ・ルン撮影 掲載許諾取得済

FN: 翻訳の仕事もしていて、自分と言語の関係をどのように見ていますか?

AL: A translator’s work reminds that of doctor Frankenstein’s, since you kill a text in one language and resuscitate it in another. You cut your victim in pieces, put them back together, and wish that they leave your clinic looking better than the patient of Frankenstein. In the process you lose some peace of mind and a lot of preconceived notions about your own language. It is a happy loss since it takes you out of the story of one specific culture and opens you up to a much bigger, common story.

Now you understand what happens under the skin and you start seeing languages beyond the superficial layer of vocabulary and its pronunciation. You see the organs and the connections between them, aka syntax, and you understand that they are just one of many options. And you start asking yourself questions. Why do some languages use definite and indefinite articles? At some point there had to be a powerful and mysterious need to divide reality into “things we know something about” and “things we know nothing about”. As someone who comes from Slavic languages, where we only see “things,” I find it fascinating that we grow up in such different realities.

AL: 翻訳者のやっている事と言ったらフランケンシュタイン博士の研究と同じ。言葉をバラバラにして、他の言語に組み直して蘇生する仕事だから。言葉を切り刻んで、つなぎ合わせて元の形に戻した後は、フランケンシュタイン博士の患者よりはマシに仕上がっていることを期待しつつ、患者が帰るのを見送っている。手術中、翻訳者は正気を失いながら、母語に抱いていた思い込みを何度も打ち砕かれる。だが打ち砕かれ続けて初めて、言語を美しく包む文化のベールがはぎ取られた後に現れる、言語同士の共通性に気づいて、言語とは何かと翻訳者は考え始めるのだ。

言語がまとう美しい肌、その下で起きている事を翻訳者は知るのだ。言語を覆う皮膚が単語や音声とすれば、その下には臓器や血管にあたる文の構造がある事を。そして構造には多数の選択肢があり、今ある構造が全てではない事も。次に、どうして定冠詞や不定冠詞を使い分ける言語があるか翻訳者は自問するようになる。いつか過去に原因は不明だが是非とも必要となって、目の前の事柄を「既知のもの」と「初見のもの」の2つに区別するようになったに違いないと考えるのだ。スラブ系言語には「初見」と「既知」の区別など無いので、言語が異なると世界はこれ程までも違って見えているのだとわかりハッとする事がある。

訳注: この話は、例えば英語では初見のものの前には不定冠詞の a/an (an apple とか) を、既知のものの前には定冠詞の the (the apple とか) を付けてもの (この場合は apple) を区別する事にふれています。

FN: 言語を習得して、自分のものにするとはどういう事だと思いますか?

AL: In Europe or the US we seem to be obsessed with “speaking” a language, the ultimate ownership as opposed to thinking, dreaming or writing in it. Beyond this narrative, which is an effect of the Western world’s dictatorship of extroversion, a language is simply a world that you choose to live in. If you live in that world, you own its language.

AL: 欧米では話せるようになる事が、言語の習得だとの考えが強い。その言語で考えたり、夢見たり、書いたりすることは、会話ほどは重要視されない。きっと社交性やフレンドリーさを盲信する西欧の嗜好なのだろうが、本当の言語とは自分を取り巻く世界の事で、自分が選んで生きていく世界のこと。そこで住人になることは、その言語の担い手のなる事でもある。

FN: この本はとても愉快ですが、一方で人によって考えの異なる微妙な問題にも触れています。帰属性、拒絶、移民、亡命、統合への希求と言った問題と言語のかかわりにつて話してくれますか?

AL: Humour is an effective narrative tool since it brings things back to proportions. When you are an immigrant the last thing that is expected from you is to be funny. If you enter another culture, you are expected to behave as if you were invited to a formal dinner at your auntie’s: sit properly, eat up what you are served, be silent and smile a lot. If you have any interest in culture, you can listen to what the auntie’s intellectual friends have to say, maybe take notes and later try to translate them for your less fortunate friends, the ones that have not been invited. What nobody expects you to do is to arrive at your auntie’s disguised as SpongeBob, sit whenever you please, eat noisily your own vegetarian burger and start telling intellectual jokes.

Equality is difficult to achieve without humour because humour itself is a form of equality.

AL: ユーモア様の愉快で偉大なお力添えがあればこそ、こじれた話も元のさやに収まると言うもの。世間が移民に一番求めているのは、ヘンに目立たず、おとなしくすること。新しい土地でうまくやるには、伯母様主催の夕食会に招かれた時のように振る舞うのです。行儀良く座って、出てきた料理は何でも平らげて、静かに、でも笑顔は絶やさずに。何か知りたいことがあっても、まずは伯母様の上品なお友達の話に耳を澄まし、書き留めておいて、その場に招かれなかった不運な同郷人に訳して説明するのです。一番嫌われるのはスポンジボブよろしく現れて、遠慮会釈なくどこにでもドンと座って、持参の肉なしベジバーガーをクチャクチャ食べながら、気の利いたつもりでジョークをかましていい気になる事。

ユーモアが通じるのはお互いを対等と思えばこそ。だから対等でいるためにもユーモアは欠かせないのです。

FN: ロス・パリンプセストスの英語版、仏語版が出版され、今度は独語版が出ます。何かの折りには自分をどう紹介されたいですか? ポーランドの作家、2冊目もスペイン語で書くからスペイン語作家、それとも単に作家が良いですか?

AL: I can be described as Jack the Ripper, if that satisfies the person describing me! I know that I will always be classified as belonging to this or that other culture, but it doesn’t mean that I need to identify with a label. In our impermanent world, nationality can seem a solid and objective category, but it is one of the least objective ones. It only describes one of your external characteristics from a historical perspective. Your passport says nothing about who you are now.

The concept of national literature is itself an extravagant one. No other art field has been divided into these categories – we don’t hear that much about “Lithuanian rock bands” or “Nigerian photographers”, do we? There is a logistic reason behind a division into nationalities, since a book is coded in a language and needs to be translated to reach audiences that don’t understand it. But once it is re-coded, the human experience it contains doesn’t differ from the one in a book published across the border. A passport itself is not a very interesting read, even if the airport queue is very long. I strongly recommend reading shampoo labels in the shower instead.

AL: たくさんの言葉を解体してバラバラにして来たから「切り裂きジャック」とでも呼んでもらおうかな。きっと私の紹介者も大乗り気かも?周りは私が何語の作家だと決めつけたいのかもしれないが、だからといって私の方はそれに付き合う必要は無い。何事もどんどん変わっていく世の中にあっても、国籍は客観的で不変に見える。だが実のところは少しも客観的ではない。国籍とは個人を経過した時間の観点から見た外見的一特徴にすぎない。自分が今何者であるかについてパスポートは何も語りはしない。

何々国の文学というのも大げさな区分だ。他の芸術にこのような区分は存在しない。リトアニアのロックバンドとか、ナイジェリアの写真家と言った区分を聞いた事があるだろうか? 確かにある言語で文字に記しても、他国で読んで貰うには翻訳する必要があるから、文学を国で分けることは記号論的には一理あるだろう。けれども、他の言語で再文字化してしまえば、本に記されたひとりの人間の記憶は、国境を超え、言語が異なっても、同じ記憶である事に間違いない。たとえ空港の審査行列は長く続いていたとしても、手にしているパスポート自身には読むに値する事は何も書かれていない。シャワーの間にシャンプーの注意書きを読む方がよっぽどためになると言っておきたい。